Beyond evidence-based design

How UX people can level-up their critical thinking

Some think that expertise and seniority in design and UX is evidence of Doing Things Properly.

In fact every newbie designer goes through a stage where they learn The Rules. And The Rules give such a sense of safety that they want to cling to them relentlessly.

What is and is not ‘robust’

The phases of a project, in what order

How long things should take

The number of rounds of testing

The ideal research conditions

The number of participants in a study

And every how-to book and article ever (including ones I’ve written no doubt)

This can become annoying for stakeholders as it doesn’t really meet the reality of modern design warfare environments.

Because as every seasoned designer knows, the level of adherence to ‘official’ ways-of-working changes by project, by stakeholder or client, by company or employer and by the problem you’re trying to solve.

And you need more than just bootcamp-level Design Thinking in your toolbox.

To be clear - I’m not saying we shouldn’t follow rigorous evidence-based methodologies. I’m saying we should have a back up plan for when we can’t.

In short, we need to flex.

Why we love the rules

One of the most attractive things about UX Design and Research is that it gives us clear guidelines to follow regarding what is and is not robust, rigorous and acceptable - much of which was set by the academics that founded the field.

It gives us a somewhat moral and intellectual North Star.

And that works well in an academic or highly rigorous environment, but can soon become frustrating to those classically trained who end up working in modern product environments or worse… Marketing agencies, where the default is just to make everything up based on f-all on the daily.

What are the rules?

There are many rules for how UX and design should be done. You just need to take a Nielsen Norman Group course to discover that.

However at the highest level, one could say there are two main requirements for evidence-based design:

We should based decisions on evidence, preferably data and primary research

We should question everything especially when we believe it to not be evidence-based.

What could we do instead.. or as well?

Now there’s nothing wrong with the two rules above. If you get to follow them every day then well done - cling on to that job as long as you can.

However when it comes to the reality of large organisation politics, minimal resource, demanding stakeholders, time limits, or no access to users, you need to think differently.

You need to engage some alternative critical thinking methods that - let’s be clear - don’t make you any less of a quality designer.

After all, good design is a balance of art and science - of evidence balanced with human creativity.

So.. what could we do instead? (or as well…)

1. Think in systems

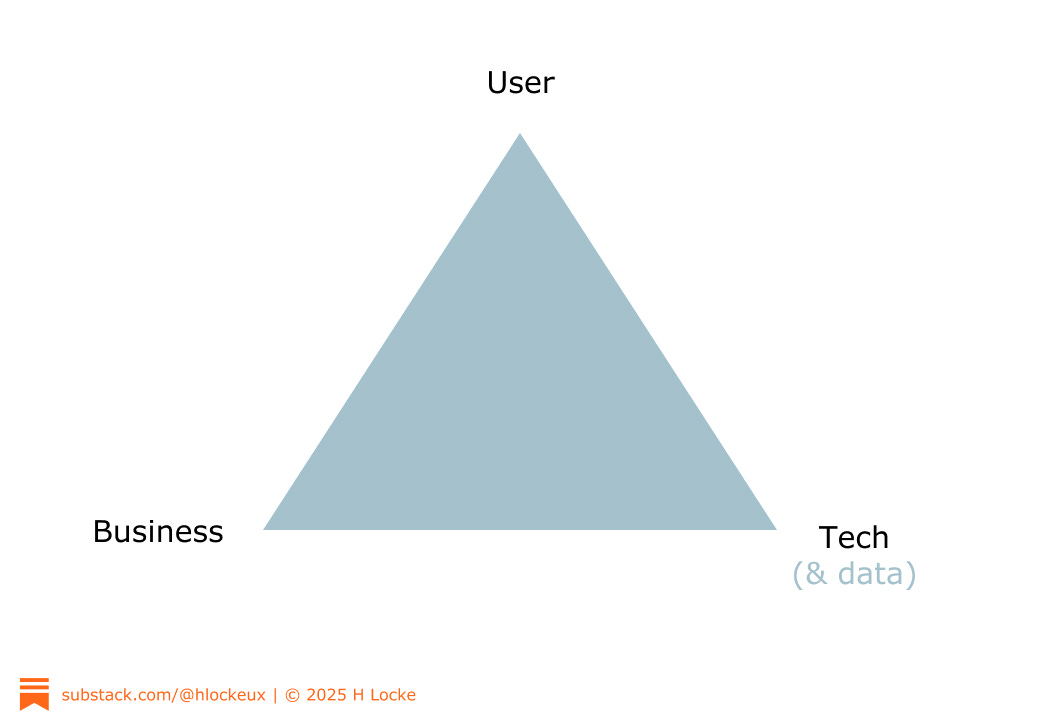

Thinking beyond users and their immediate needs allows us to consider the wider experience ecosystem. This can include business context, technical constraints, market trends. It can include social factors, inclusion, sustainability or ethics.

Any of these factors could also be impacting your wider user experience.

Or speed up your stakeholders’ decision-making processes.

Or identify hitherto unknown dependencies.

Yes you’re getting into the realms of service design and no your stakeholders might not want you faffing around in this space instead of popping out the UI they asked for but they can’t stop you thinking. And the minute your new approach adds value to the outcome of the work, they’ll want more of it.

🧽 I’ve got a new post coming up soon on Systems Thinking. Be sure to subscribe to receive that one when it drops.

2. Use your intuition and expertise

Not everything has to be 100% proven before you act at all.

If you’ve read my previous article on ShuHaRi then you’ll know that early stage, inexperienced designers often cling to methodologies and rules. This can include things like how many participants you need, how and when to run research - when we all know that there are times that you have to be pragmatic and flexible because maybe your participants are hard to reach.

And this is a real thing.

I recently heard about a “senior” designer being released from a contract because they were being too purist in their approach. And it wasn’t because they were highly experienced. It was because they were not strong enough in research to know when to be pragmatic and flex methods to accommodate stakeholders’ and organisational reality.

While evidence is critical to major design or business decisions, experienced designers know that not every decision in every design process can be fully validated before implementation.

Sometimes you need to follow best practice plus your own experience of previous design and research projects.

Sometimes you need to trust your instincts and make informed decisions based on the research and evidence you already have.

Examples -

If you are working in an ambiguous or fast-moving environment the research may not get done fast enough to be used

If you are making minor tweaks to colour contrast or button size and you know best practice will take you most of the way there

If you are doing anticipatory design, and you can’t really predict how a product or service will perform or be used in the future real world

If you have other data, but not the kind of research you’d ideally like to do in a perfect world.

Sometimes, you need to trust your expertise and make somewhat informed bets.

Sometimes you need to prototype and iterate rapidly with small groups of users to get just enough information to keep moving forward.

Now of course the answer to when to use evidence and when to use intuition is .. It Depends.

The answer is somewhere between make-it-up and academic-level research. Only experience (your own, or a more senior person around you) can really help you make this kind of judgement call.

3. Think before you question (everything)

Questioning everything is a really easy mantra to stick to. It sounds like you’re a scientist. But questioning everything without coming up with a reasonable next step, action or alternative thought can be.. unhelpful.

It can also make you unpopular or seen as a person who sees only problems not solutions.

Instead, frame your questions as hypotheses based on existing knowledge and test them systematically.

For example when stakeholders request a new feature, rather than asking WHY a hundred times, frame it into a testable hypothesis - and then get on and test it.

"We believe this feature will address X user need and improve Y metric. We will validate this by conducting A/B testing or usability testing."

By tying the hypothesis to specific metrics and measurable outcomes, you have a clear way to show that the question was answered as well as asked.

4. Manage trade-offs

There are very few projects that aren’t riddled with contradictions and dependencies. Understanding them can be the difference between strategic design partner and UI monkey.

Rather than asking ‘why’, uncover competing priorities between user needs, business goals and technical feasibility.

Be the person that finds them, debates them, documents them and drives decision-making and alignment.

Use tools like

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to It Depends... to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.